With the second round of group stage matches complete at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, knockout round qualification is becoming clearer. Several teams have already clinched their spots past the group stage, with a few more near locks to do so on the final match day. There are, however, still a few groups with something left to play for, ensuring dramatic matches during this next week. After running the latest batch of Monte Carlo simulations with my World Cup model to estimate each country’s chances of advancing to the knockout round, I noticed a few neat probability quirks that reveal a lot about which groups are sure to provide viewers with the most exciting final match day.

Group F

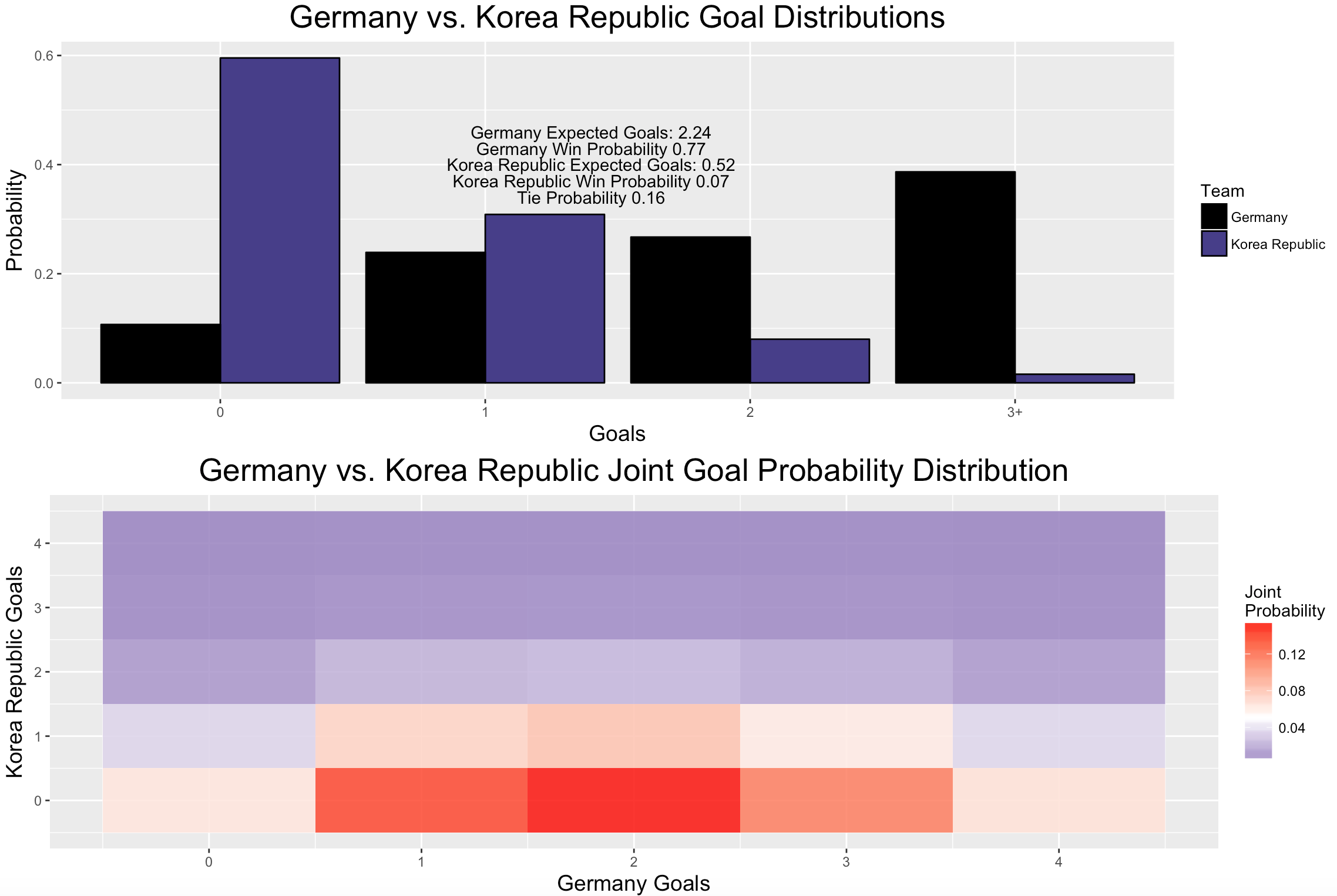

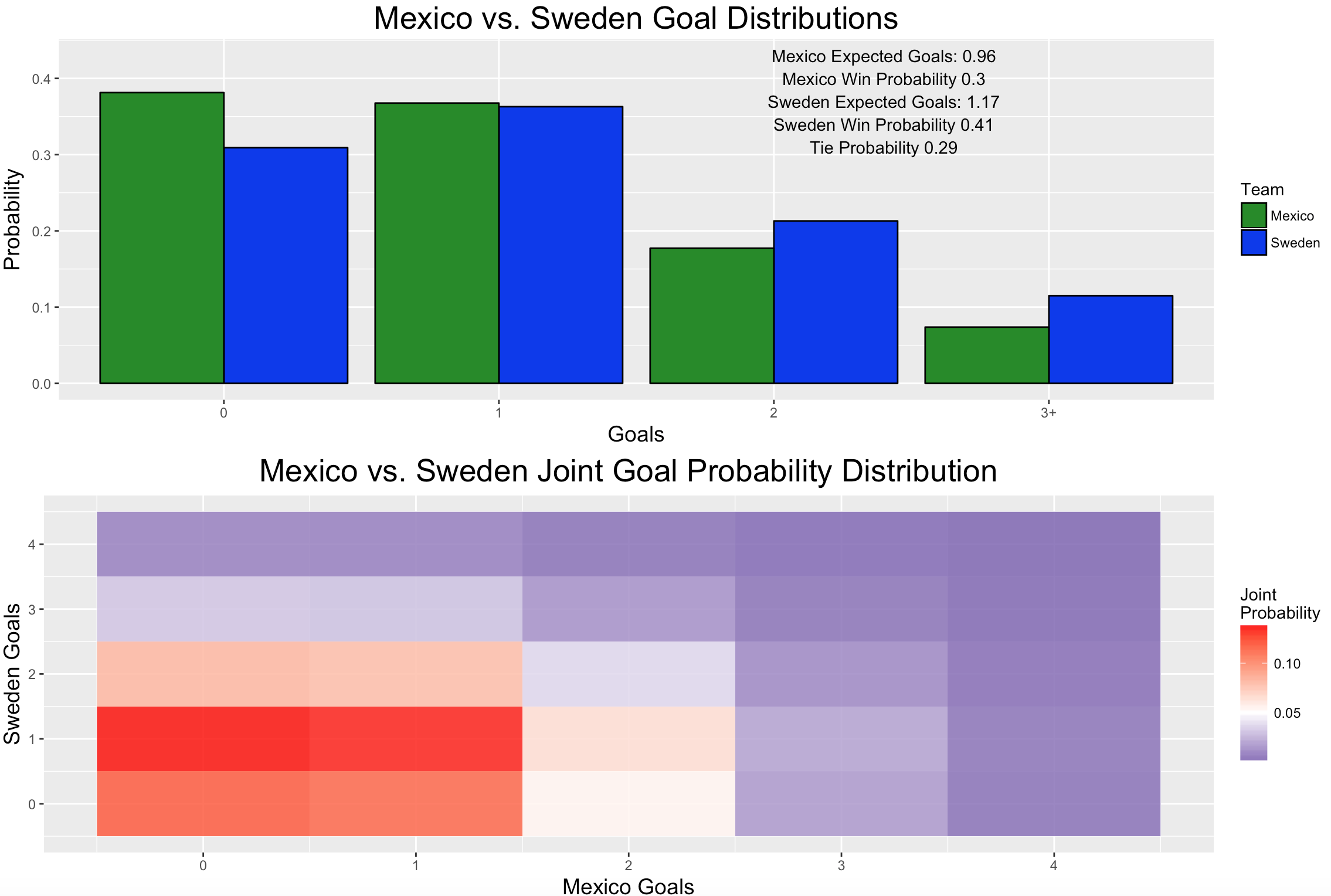

After Toni Kroos’ last gasp winner over Sweden, it’s not exactly groundbreaking to suggest that Group F, comprised of Mexico, Germany, Sweden, and South Korea, will offer one of most exciting endings of any group. All four teams are still alive heading into the final round of matches, meaning everyone’s best squad will be on display. Yet, that’s not the primary reason this group caught my eye. Rather, Group F really caught my eye when I looked at the group standings after 10,000 simulations.

## country group expected_pts first_in_group second_in_group r16

## 1 Germany F 5.48 0.2164 0.6196 0.8360

## 2 Mexico F 7.24 0.6055 0.1071 0.7126

## 3 Sweden F 4.47 0.1781 0.2541 0.4322

## 4 Korea Republic F 0.36 0.0000 0.0192 0.0192Interestingly, despite leading the group with 6 points, Mexico does not possess the best chance to advance, and frankly, it’s not really that close. According to my model, Germany is about 13% more likely to move on than Mexico. FiveThirtyEight founder Nate Silver noted the same quirk on Twitter. What makes this really interesting, is that Mexico is nearly 3 times as likely as Germany to win thr group, and get roughly 1.7 more points than Germany on average. How is this possible? It all boils down to conditional probability. First, recall the law of total probability. If is an event, and are a disjoint parition of the of the sample space, then In the contest of the World Cup, we can think of as being the event that Mexico advances, and , and being the events that Mexico wins, ties, or loses its final match against Sweden. Then, we have

Mexico is guarteed to win the group with a win or a tie against Sweeden, so . With a loss however, Mexico’s position is much more precarious. Full scernarious are outlined here, and Mexico can still advance with a loss, but accoring to my simulations, is only about 25%. Conditional on the fact that Mexico loses, they would lose any head to head tiebreaker Sweden, meaning a Germany win over South Korea would almost certainly eliminate El Tri. As for Germany’s favorable odds, a simple look at the expected goal distirbution for the final two matches expain why my model suggests Mexico isn’t as safe as one might’ve thought.

Group H

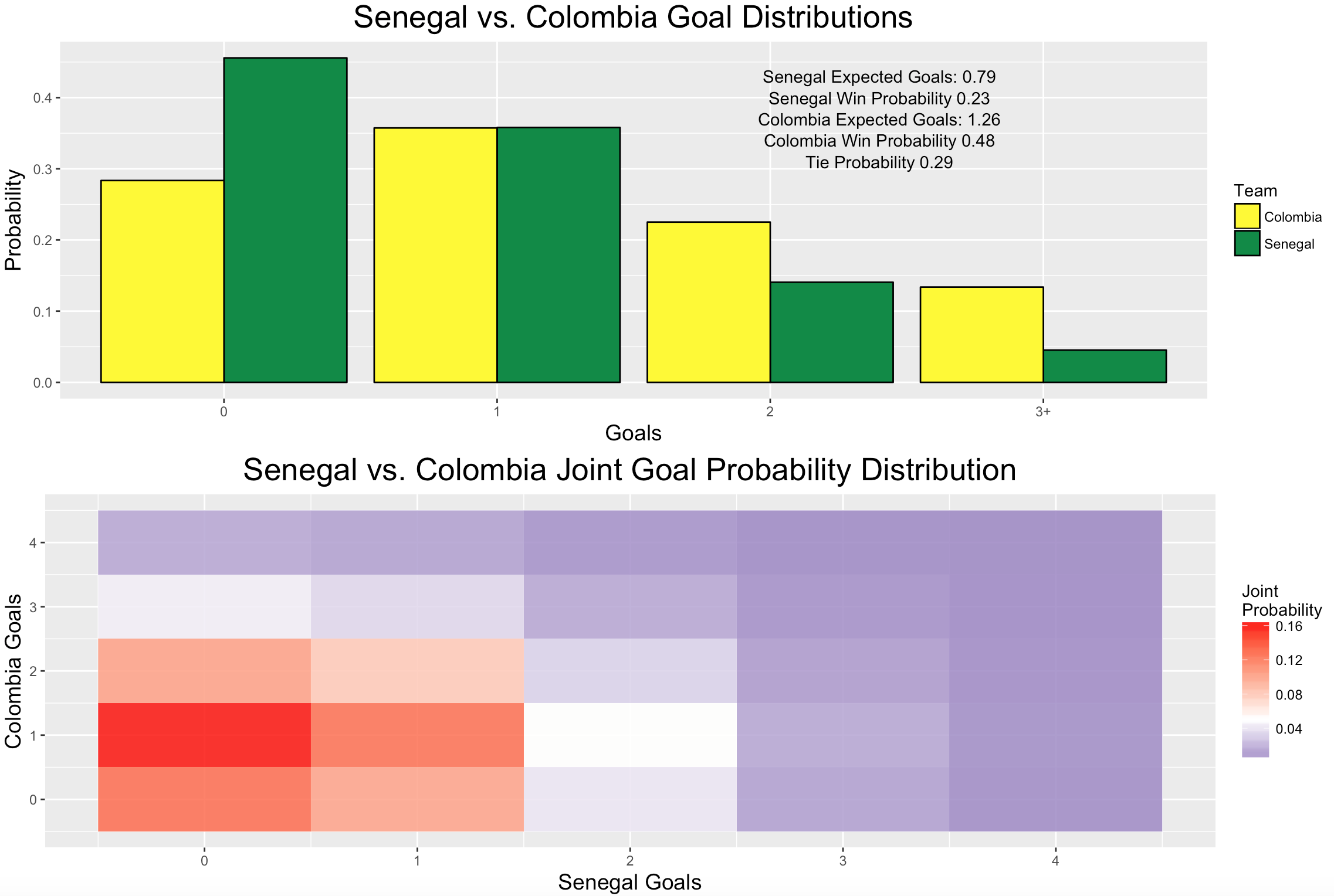

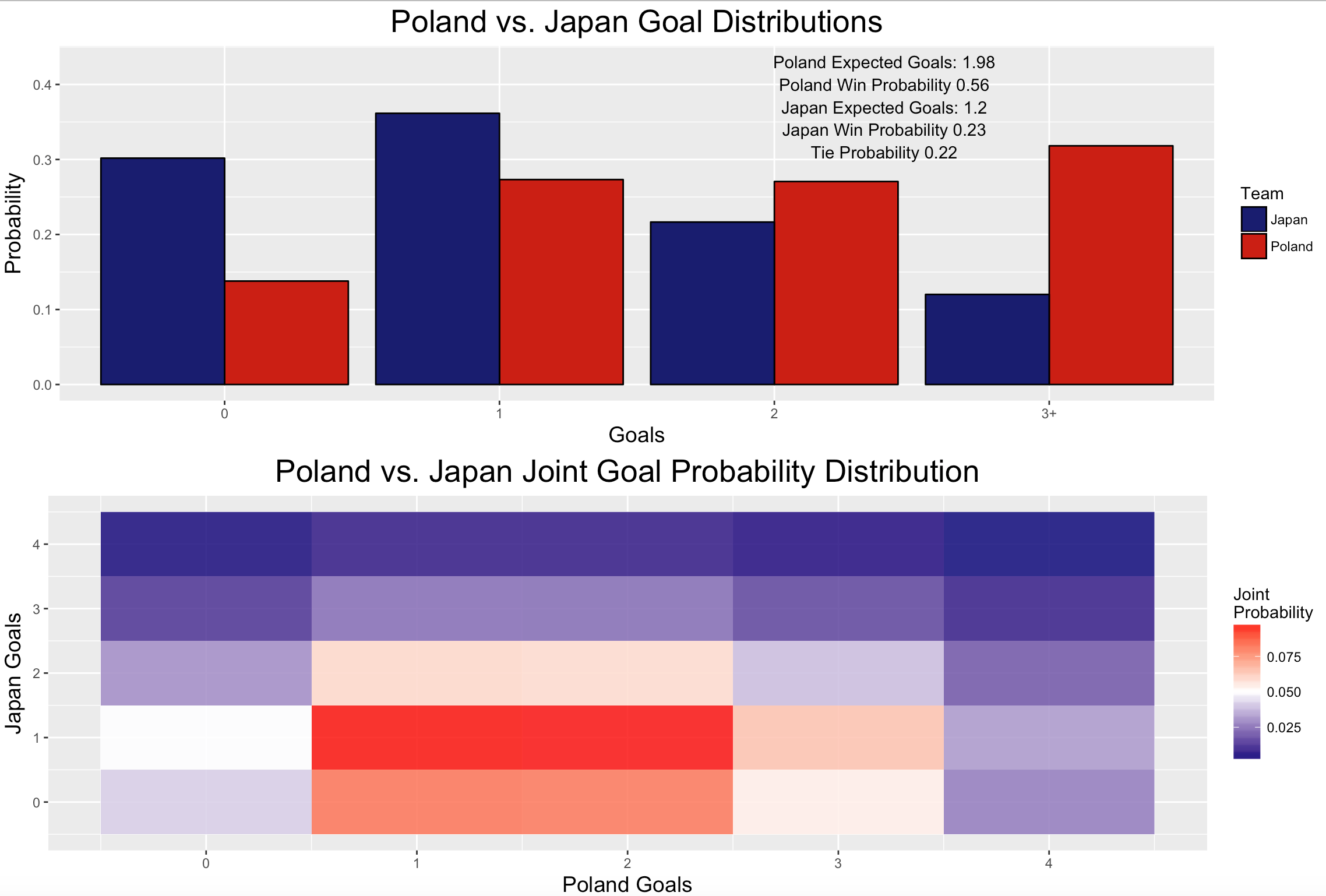

The other interesting group from a probability standpoint is Group H, comprised of Senegal, Poland, Japan, and Colombia. While Poland has been elimanted from the World Cup, the other three squads have a good will fight on the final match day for two spots in the knockout round. Here’s how the simulations see the group shaking out.

## country group expected_pts first_in_group second_in_group r16

## 1 Senegal H 5.94 0.5168 0.2633 0.7801

## 2 Japan H 4.71 0.2340 0.2608 0.4948

## 3 Poland H 3.36 0.1338 0.2807 0.4145

## 4 Colombia H 2.91 0.1154 0.1952 0.3106We see two things about this that are noteworthy.

- Japan, Senegal, and Colombia are all each more likely to advance than not despite the fact that one of them will not advance.

- All three of the those countries are essentially a 2/3 chance of advancing.

At first, 1. might seem somewhat paradoxical, but actually it’s quite reasonable. After all as there are 2 spots in the knockout round for each group. Given that Poland has already been eliminated, we must divide that 200% of probability amongst 3 teams somehow, and doing so in a relatively even manner yields this neat result. Micah McCurdy has a good explanation on this phenomon in general. Perhaps even more interesting is the fact that the three remaining countries’ chances don’t deviate significantly from a true random draw, in which each country’s chances would be exactly 2/3. Any time you have random or near random events in sports, it’s almost always exciting (this is why we find March Madness so appealing, for instance), meaning that Group H’s final matchday will be must-see TV. Here’s how my model sees the final Group H matches.3